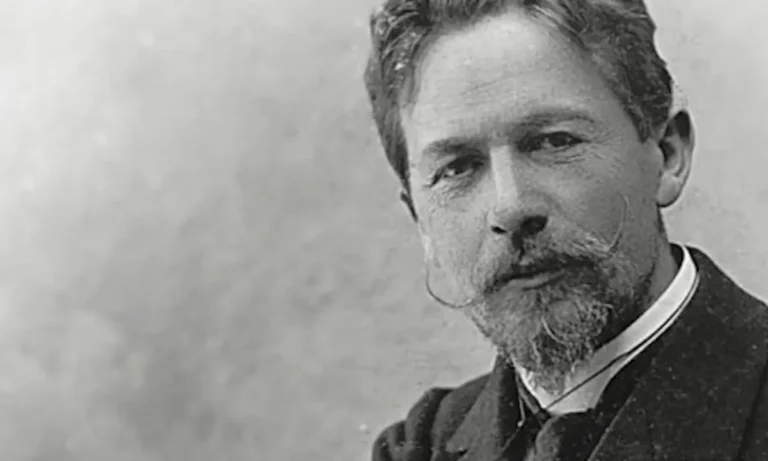

Antonis Katsantonis: The Eagle of Agrafa who never bowed to Ali Pasha

In the misty mountains of Agrafa, a lone rebel became a legend. Antonis Katsantonis – known as the “Eagle of Agrafa” – waged a guerrilla war against Ali Pasha’s oppressive rule in the early 1800s.

In the mist-shrouded peaks of Agrafa, an eagle soars above ancient forests as dawn breaks. For the Greek highlanders below, that eagle came to symbolize a man – Antonis Katsantonis – whose defiance of tyranny would make him a legend. Born around 1775 in a humble shepherd’s family in the Agrafa mountains, Antonis Katsantonis (originally named Antonis Makriyannis) grew up under the shadow of Ottoman rule. As a young man, he experienced an injustice that lit the fire of rebellion within him. In the late 1790s, an Ottoman official accused Katsantonis’s family of stealing livestock – a false charge concocted by a local henchman of the region’s despot, Ali Pasha. The 23-year-old Antonis was seized, beaten, and dragged in chains to Ali Pasha’s stronghold in Ioannina. Only after his father paid a hefty ransom did Ali Pasha agree to release him. Humiliated but unbroken, Antonis returned to his mountain home vowing to “wash away” the dishonor. He fled to the hills and embraced the life of a klepht – an outlaw freedom-fighter – determined to take revenge on the oppressors and restore his family’s honor.

For his bravado and newfound calling, Antonis soon earned a new name. His exploits impressed his baptismal godfather, an aging klepht captain named Vasilis Dipla, and the young man made no secret of his desire to join the guerrilla fight. But Antonis’s mother, Aretí, desperately wanted to keep her son out of harm’s way. “Káτσε, Αντώνη” – “sit, Antonis, stay” – she would plead whenever he spoke of going to war. The mother’s plaintive refrain “kátse Antoní” became a teasing nickname among those who knew the bold youth. Thus, Antonis Makriyannis became known as “Katsantonis” – literally “Sit-Antonis” – the very name under which he would pass into history.

Having cast off his old life, Katsantonis headed to the mountains and assembled a band of fellow klephts. He knew the crags and forests of Agrafa intimately, and he used that knowledge to harass the Ottoman authorities at every turn. By the early 1800s, tales of the daring young klepht spread from village to village. The once obscure shepherd’s son had become the most famous rebel leader in Agrafa and the surrounding regions of Evrytania and Aetolia. His name was spoken with admiration by the enslaved Greek peasants – and with hatred by the Turkish and Albanian garrisons he defied.

War Against Ali Pasha

Before long, the escalating rebellion in the mountains drew the full attention of Ali Pasha of Ioannina – the powerful Ottoman governor whose iron-fisted rule earned him the nickname “the Lion of Ioannina.” Ali Pasha was enraged that a ragtag klepht was brazenly challenging his authority and disturbing the order in this remote corner of his domain. He dispatched troops on multiple occasions to hunt down Katsantonis and his band. Yet in the wild terrain of Agrafa, the Pasha’s forces found themselves outmatched. Katsantonis knew every hidden path, every cave hideout. Again and again, his small guerrilla squad ambushed larger Ottoman detachments and then melted away into the wilderness. Ottoman commanders grew frustrated and Ali Pasha’s fury only grew.

Determined to make an example of the rebel, Ali Pasha resorted to terror against Katsantonis’s loved ones. He ordered the capture of Katsantonis’s elderly parents. In an act of cruel retribution, Ali’s men tortured and killed the couple, hoping the loss would break the will of their son. When news of his parents’ murder reached him, Antonis Katsantonis did not bend – he swore a sacred oath over their memory that he would avenge them. From that moment on, his fight against Ali Pasha became deeply personal. The mountains of Agrafa erupted with a renewed fury as Katsantonis and his klephts struck back at Ottoman outposts with vengeance in their hearts.

Ali Pasha, infuriated and increasingly desperate, is said to have raved about the elusive rebel who defied him. He reportedly shouted at his officers, “Can no one bring that man to heel? That Katsantonis has become my nightmare!” The Pasha put a bounty on Katsantonis’s head and sent some of his best commanders to crush the Eagle of Agrafa once and for all.

One of those commanders was Veli Gega – remembered in folk tradition as the fearsome Veligekas – Ali Pasha’s most trusted Albanian enforcer. In 1807, Veligekas marched into the Agrafa highlands at the head of a crack detachment, determined to succeed where others had failed. Katsantonis did not run or hide. Instead, he prepared an audacious trap. High on the slopes near a spring called Krya Vrysi, Katsantonis and his men confronted Veligekas’s force. Rather than risk all-out battle, Katsantonis issued a bold challenge: he called out Veligekas to face him in single combat, man-to-man, to decide the outcome. The hulking Veligekas accepted. In full view of both armies, the wiry Greek klepht and Ali Pasha’s fearsome champion fought a duel to the death on the mountainside. When the dust settled, Veligekas lay slain – cut down by Katsantonis’s blade and bullets. A cheer went up among the Greek rebels and villagers: the invincible Veligekas had fallen to their hero. Songs around the campfires soon celebrated how “in the mountains and forests, the klepht’s bullets found their mark,” felling the tyrant’s mighty warrior.

The death of his prized commander plunged Ali Pasha into grief – and furious resolve. This was the greatest blow Katsantonis had dealt the Pasha so far. Ali is said to have worn black in mourning for Veligekas, even as he vowed revenge. Katsantonis, meanwhile, had reached the peak of his fame. During these years he won battle after battle against the odds, becoming a beacon of hope for the enslaved Greeks. It was said that even the legendary heroes of the time acknowledged Katsantonis’s leadership. In mid-1807, a council of Greek klepht captains and revolutionaries – including famed names like Theodoros Kolokotronis, Georgios Karaiskakis, and Kitsos Tzavelas – met on the island of Lefkada. There, by unanimous acclaim, they hailed Antonis Katsantonis as the chief captain of the klephts. The once lone outlaw was now recognized as a foremost leader of the resistance against Ottoman tyranny.

Betrayal and Martyrdom

Fate intervened at the height of Katsantonis’s guerrilla war. In 1808, a sudden bout of smallpox struck him down. The deadly disease ravaged his body, leaving the formidable fighter frail and feverish. Realizing he could no longer lead his men in that condition, Katsantonis passed command of the Agrafa klephts to his brother, Kostas Lepeniotis. With his second brother, Giorgos (“Yorgos”) Chasiotis, and a handful of the most loyal pallikaria (fighters), Katsantonis retreated into hiding to recover. They took shelter in a remote cave near the Monastery of St. John in the mountains, hoping that Ali Pasha’s wrath might pass over while the rebel lay on a sickbed.

But Ali Pasha’s determination to destroy Katsantonis never wavered – and ultimately, betrayal accomplished what force of arms could not. Acting on a tip from an informer (some say it was a local shepherd bribed by the Turks; others blame a traitorous monk or a woman who brought food to the hideout), Ali Pasha’s forces discovered the secret cave. One of Ali’s captains, a man named Ago Vasilis (or Vassiaris), surrounded the refuge with 700 armed men. In the dead of night, torches and musket barrels ringed the cave where Katsantonis lay ill.

Realizing the trap had closed on them, the klephts inside prepared to make a final stand. Katsantonis, burning with fever and barely able to lift his head, understood that capture was now inevitable. Not wishing to be taken alive, the proud chieftain begged his brother to kill him on the spot and save himself, so that at least one of them might escape. Giorgos Chasiotis refused outright. Instead, as the Ottoman troops began to rush in, Giorgos hoisted his sick brother onto his back. With pistols and swords in hand, the remaining klephts burst out of the cave in a desperate bid to break through the enemy lines. A wild melee ensued on the moonlit mountainside. Even weakened, Katsantonis fired whatever shots he could while clinging to his brother’s shoulders. The klephts fought ferociously – they knew the terrain and had the courage of despair on their side – but they were vastly outnumbered. One by one, they fell or were wrestled down. At last, after a brief fierce struggle, Antonis Katsantonis and Giorgos Chasiotis were overwhelmed and captured alive.

The Pasha’s soldiers bound Katsantonis and his brother in heavy iron chains. The Eagle of Agrafa had been finally brought to earth. Guards dragged the prisoners on foot toward Ioannina. Along the route, some say a band of Katsantonis’s comrades – possibly fighters from Karaiskakis’s company – attempted a rescue ambush, but they came too late. The captives arrived in Ioannina, destined for a dreadful audience with Ali Pasha.

In Ali Pasha’s citadel, the ailing Katsantonis was hauled before the man who had hunted him for years. Ali Pasha at first feigned a kind of admiration and offered the battered rebel leader a shocking clemency. If Katsantonis would swear loyalty to him and serve as an armatolos (a militia chief) under Ottoman command, Ali would spare his life and even give him authority over Agrafa once more – this time as the Pasha’s vassal. Here, at last, was the chance to save himself: all Katsantonis had to do was bow and accept Ali Pasha’s terms.

Even chained and beaten, Antonis Katsantonis’s spirit remained unbroken. The legendary klepht – who had fought so fiercely for freedom – looked his enemy in the eye and flatly refused the offer. He would not bend the knee to Ali Pasha, not even to save his own life. Some accounts say he invoked the memory of his slaughtered family and the oath he swore on his mother’s grave, telling Ali that he could never betray those principles. Like many other Greek heroes of that era, Katsantonis chose to die on his feet rather than live on his knees.

Ali Pasha’s face darkened with rage at this defiance. If Katsantonis would not submit, the Pasha would make him an example that all of Greece would remember. The governor pronounced a sentence of exquisite cruelty. On September 28, 1808, the people of Ioannina were summoned to the fortress to witness the fate of the notorious brigand who had defied Ali for so long. Katsantonis and his brother were led out to the castle courtyard, where a large plane tree stood. There, Ali’s executioners – blacksmiths by trade – had placed a black anvil on the ground. Katsantonis was stripped and forced down onto the anvil. At the Pasha’s signal, the executioners raised their sledgehammers and brought them crashing down onto Antonis Katsantonis’s limbs. A hush fell over the crowd, broken by the sickening sound of bones shattering. Blow after blow, the executioners methodically smashed the heroic klepht’s arms and legs. The torture was ghastly and drawn-out, intended to inflict maximum pain. Yet, as the legend goes, Katsantonis never screamed or begged. Some say that through gritted teeth he defiantly sung a klephtic dirge – a final act of resistance – until a hammer strike at last silenced him. After enduring unimaginable agony, Antonis Katsantonis died on that anvil, eyes turned toward the sky. He was 33 years old. His brother Giorgos Chasiotis was spared the torture; he was beheaded swiftly beside Katsantonis’s broken body.

Legacy

The Ottomans had hoped that the horrific execution of Katsantonis would terrorize the Greeks into submission. Instead, it only fanned the flames of resistance. Antonis Katsantonis entered history as a martyr – a symbol of the Greek people’s yearning to be free. His unyielding courage in the face of death inspired his compatriots far and wide. In fact, popular tradition holds that fifteen years later, during the Greek War of Independence, the renowned Souliot captain Markos Botsaris avenged Katsantonis by slaying the very Ottoman officer who had captured him. True or not, such stories show how deeply Katsantonis’s tale resonated with those who fought after him.

Across Greece, folk songs and ballads immortalized the Eagle of Agrafa. These songs mourned his tragic fate and praised his bravery, ensuring that even illiterate villagers in far-off provinces knew the name Katsantonis. Poets likewise took up his story – notably Aristotelis Valaoritis, who wrote a moving poem about Katsantonis’s final moments and indomitable spirit under torture. In the realm of popular culture, Katsantonis’s saga has been retold through the Greek shadow-puppet theater (Karagiozis), and a television docudrama series in the 2000s brought his biography to the screen for modern audiences.

Historians regard Antonis Katsantonis as a crucial precursor to the 1821 Greek War of Independence. Decades before the organized revolt, his guerrilla struggle embodied the ideals of freedom and defiance that would later fuel the revolution. He showed that the Ottoman Empire’s yoke was not unbreakable – that even a lone mountain klepht could challenge an empire, at least for a time. In his homeland of Agrafa and throughout Greece, his legacy endures. A life-size wax figure of Katsantonis on horseback stands in the Pavlos Vrellis Museum of Greek History near Ioannina, not far from where he met his end. Around the country, statues and busts of Katsantonis honor his memory in town squares, and numerous streets, schools, cultural clubs, and events bear the hero’s name.

Perhaps most fitting of all, the Greek folk tradition remembers Antonis Katsantonis with the soaring nickname “ο Αετός των Αγράφων” – “the Eagle of Agrafa.” It is a tribute to how he lived and how he died: proud, free, and untamable to the very last breath. The Eagle of Agrafa never bowed to Ali Pasha, and his legend continues to fly high in Greece’s collective memory.

Sources:

wikipedia

mixanitouxronou

sansimera

kathimerini

evrytanika

greeklegendsandmyths

vrellis

tovima